a book by adel bishtawi

The story of natural numbers

3rd Edition

From a review by BLUEINK: Along with exploring the earliest systems of counting, the book offers a frequently fascinating overview of ancient trade and linguistics. The narrative– which is enhanced by tables, charts and illustrations–takes place in Egypt and throughout the Middle East, with an emphasis on Arabia and side-excursions to Sicily and Andalusia, then eastward to India

—————————————————–

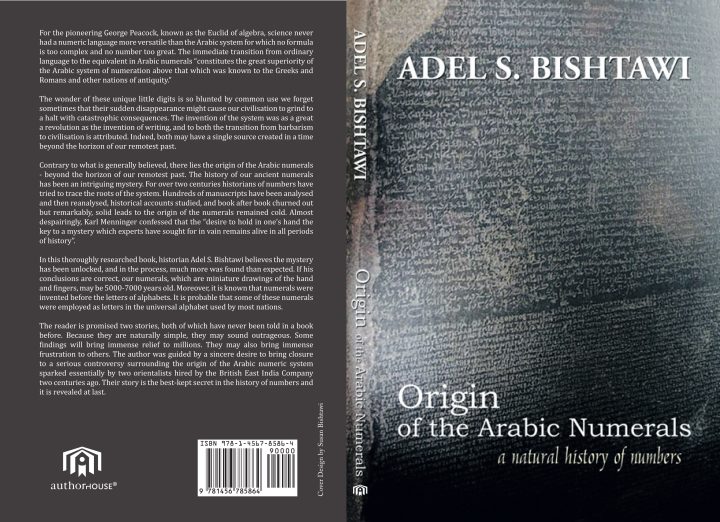

We have two stories to tell, both of which have never been told in a book before. Because they are naturally simple, they may sound outrageous. This should not be of concern, since shocking one’s readership with simple facts is one reason why many authors write their books. We are confident that most of what we have discovered in the course of our original research is correct, but we have no problem at all with readers calling our assertions ‘claims’ until they can be evaluated by other experts who are better suited to judging the significance of what we have found. Some of our findings will bring immense relief to millions. They may also bring immense frustration to others. We were guided in our research by a sincere desire to bring closure to a serious controversy that was sparked essentially by two orientalists hired by the East India Company two centuries ago.

Their story is the best-kept secret in the history of numbers and now is a good time to reveal our findings. For this reason, we decided to provide an English version of the book that was originally prepared in Arabic, a time-consuming and laborious undertaking, and not without its faults. The temptation to rewrite large sections of the book was strong. However, the scope of our research was extended unexpectedly, and the confidentiality of our work was compromised. This book, therefore, should be considered as a first attempt to present a complex argument in the clearest terms possible, and not to subvert established histories.

The best reward for our many months of arduous work is for this contentious issue to be settled conclusively once and for all, but we are not certain that all those involved will see it this way. We are fully aware that a great deal may be at stake. The possibility that an entire historiography could be exposed as a construct founded on narrative and misunderstood concepts is unlikely to be acceptable. For this and other reasons, we expect to be criticised. This is fine with us. Before a story is told, one must be prepared to tell it. If the price for telling it is criticism, then so be it.

Our other story is much older, simpler, and therefore potentially more outrageous. If we are correct, it may be one of the oldest stories ever told about those little ‘things’ that are so essential to human civilisation, the sudden dissipation of which could cause it to grind to a halt. Symbols that can be recognised by a computer must be special. Symbols that can be recognised by monkeys must also be special, but symbols that can be recognised by machines, apes and humans must be the only universal script invented by human beings in a time beyond the horizon of our remotest past. Speech is rightly described as one of the main discoveries that changed history: writing is the other, and both were essential tools for the creation of civilisations and the recording of history. Sadly, neither of our stories was recorded. An account claiming the non-Arabic origination of our numeric system was proven by our research to have been false. It was merely one of several other stories constructed by a number of orientalists and debunked by new research.

How old the universal numeric system we use today is we cannot say. What can be said is that most of our numerals have an ancient Arabian origin, and they even exhibit close connections with ancient Egyptian, an old dialect of a‘mother tongue’ in its earliest form before it was temporarily separated from its linguistic sister tongues across the Sinai and the Red Sea. This may also sound outrageous. Like so many issues related to the Middle East, the Egyptian antiquity is controversial due mainly to biblical traditions. Attention in the 19th century shifted suddenly from how magnificent the ancient Egyptian civilisation was, to how dazed the Egyptians were by their strong sun. Out of this dichotomous argument, a new classification of Middle Eastern cultures emerged: Afro-Asian. The eminent and independently-minded scholar Philip Hitti is in no doubt that around 3500 BC, a migration from the Arabian Peninsula forked at the Sinaitic peninsula to the fertile valley of the Nile and “planted itself on top of the earlier Hamitic population of Egypt, and the amalgamation produced the Egyptians of history. These Egyptians laid down so many of the basic elements in our civilisation. It was they who first built stone structures and developed a solar calendar.”[1]

Ancient Egyptian shares with ancient Arabian or Proto-Semitic languages “triconsonantal roots, phemic-phonetic elements (such as the diversity of guttural sounds), feminine nouns and second-person verbal forms ending in –t, gemination (doubling) of the middle radical… similarities of the pronominal suffixes and the independent personal pronouns, performative elements (such as the S-causative and the N-reflexive), and many similarities in etymology.”[2] To all this must be added one of the main characteristics of languages related to the ancient mother tongue, that is the right-to-left writing and reading of Hieratic and Demotic and the ability to write and read hieroglyphic writing and numerals from right to left or horizontally.

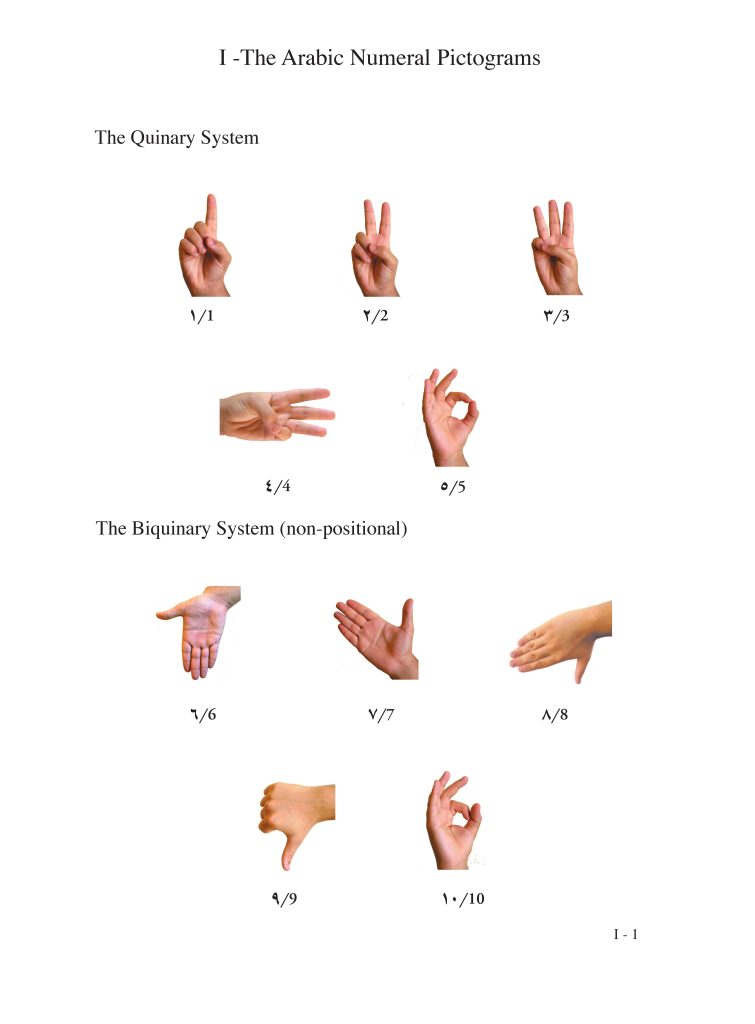

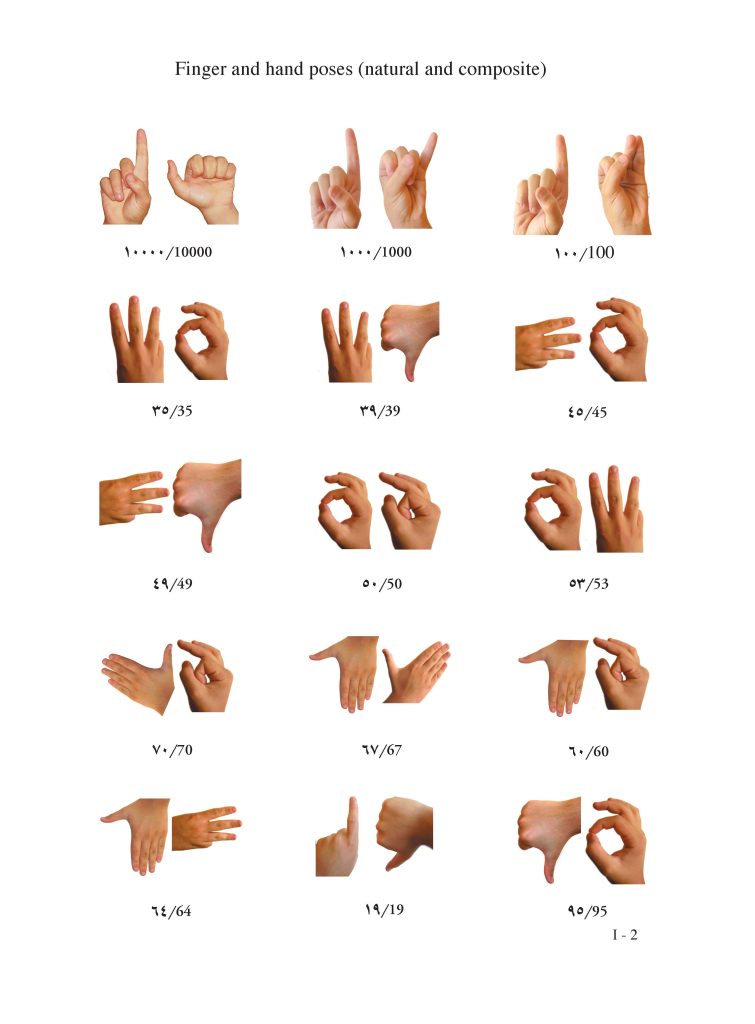

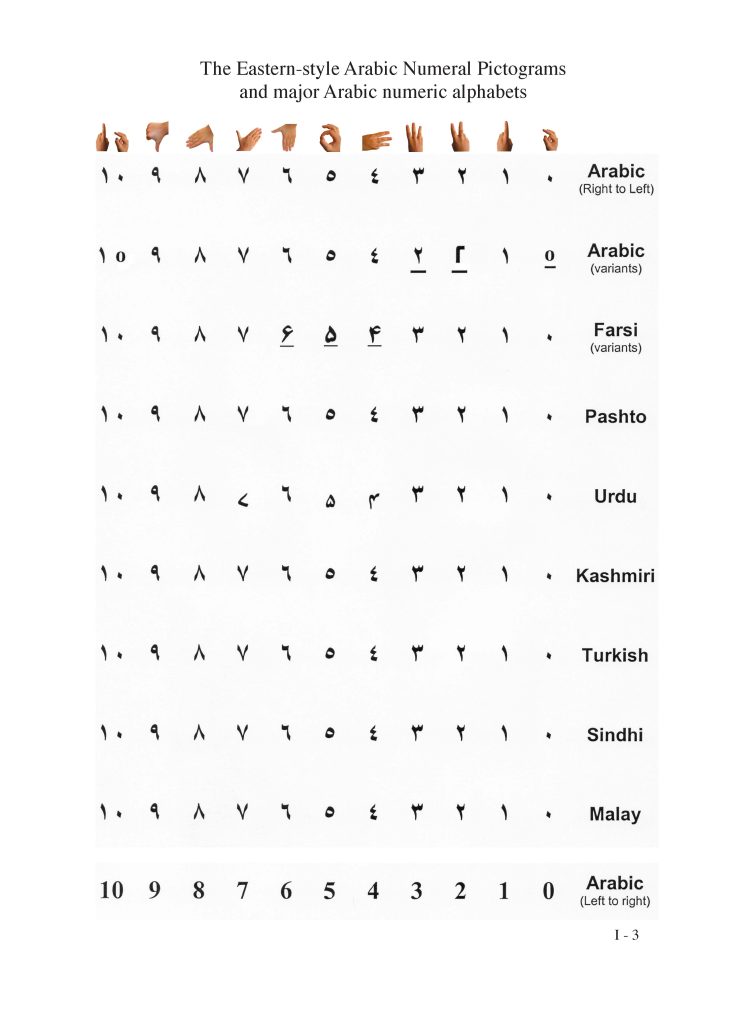

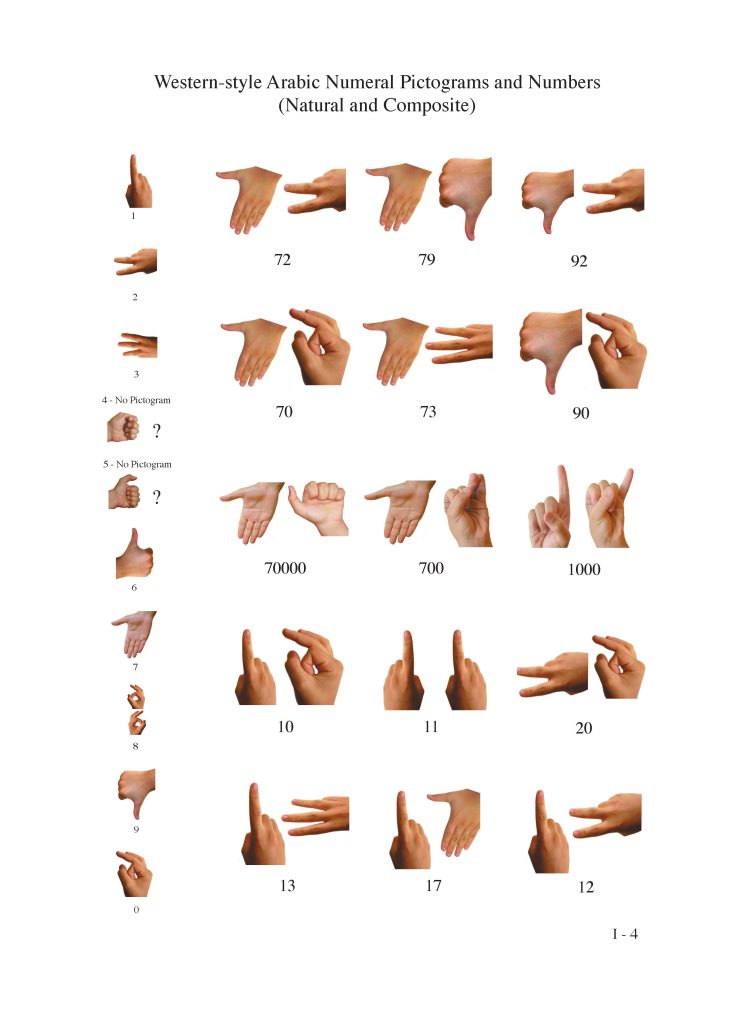

Many of the clues to the origin of our numeral system are found in Proto-Semitic, and the original meaning of the number ‘one’ in some of the descendent languages of that great mother tongue is ‘finger’. How old the mother tongue of the ancient Arabians or Semites is, again we cannot say. What is commonly known and professed by experts, however, is that early written symbols were based on pictograms that appeared around 5000 BC in different parts of the world including the Arabian peninsula, Egypt and certain parts of the Mediterranean. Our numerals are often described as ‘symbols’, ‘glyphs’, ‘forms’, ‘ideograms’, and several other terms. However, they are not any of these. Except for the zero which doubles as an ideogram, every numeral in our system is a pictogram, one of the oldest forms of miniature drawings known to have been used by our ancestors several thousand years ago. The system we often describe as ‘modern’ may turn out to be the oldest numeration system in history.

The history of the Arabic numerals, exact as the sciences employing them, is the natural history of numbers.

[1] Philip Hitti, History of the Arabs, (10th Edition, 1974), p. 10.

[2] Geoffrey W. Bromiley, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E-J, (1995), p. 33.

Text: Excerpts from a review by blueink

Numerals: A Natural History of Numbers

Adel S. Bishtawi

Publisher: AuthorHouse Pages: 359 Price: (paperback)

$18.73 ISBN: 9781456785864Reviewed: January, 2012Author Website: Visit

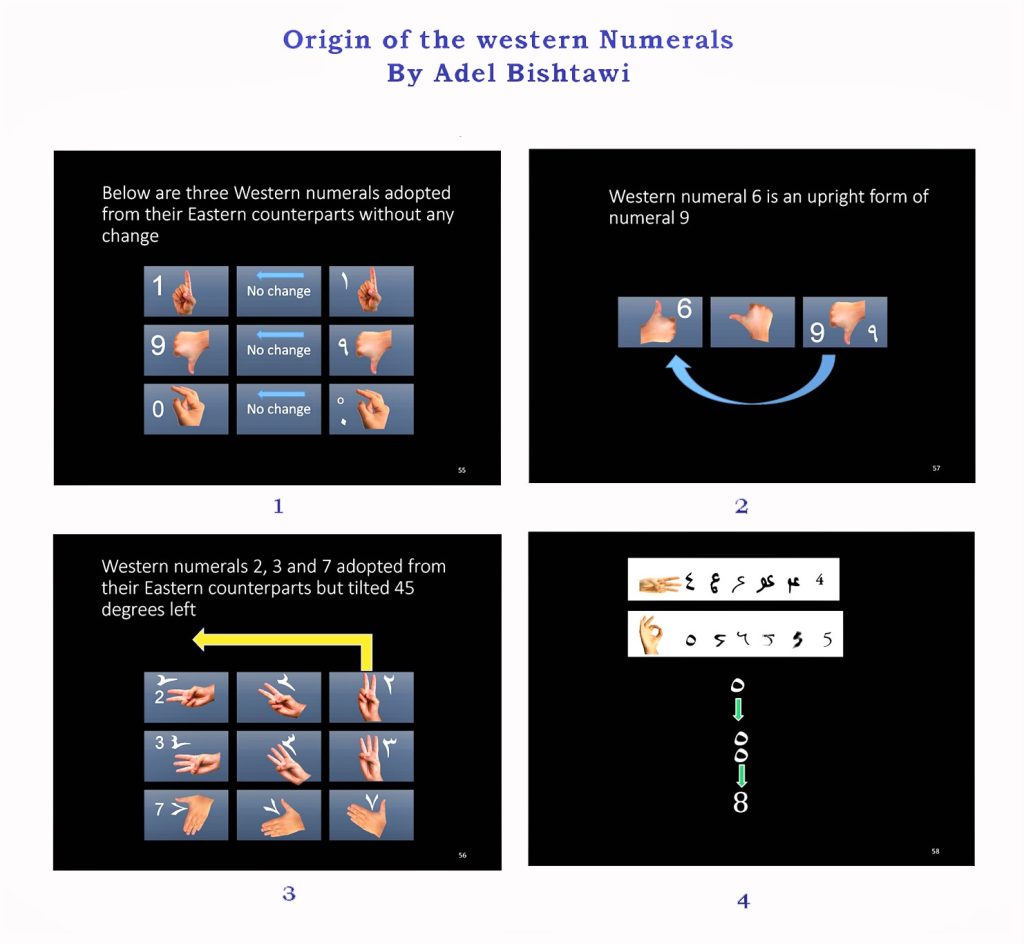

Born in Nazareth, Palestine, Adel S. Bishtawi has published short stories, novels, histories, and hundreds of articles and interviews in Arabic and English. In addition to printed material, his resume includes TV documentaries. Origin of the Arabic Numerals is a scholarly attempt to trace the numerals back to ancient hand and finger signs.

Along with exploring the earliest systems of counting, the book offers a frequently fascinating overview of ancient trade and linguistics. The narrative– which is enhanced by tables, charts and illustrations–takes place in Egypt and throughout the Middle East, with an emphasis on Arabia and side-excursions to Sicily and Andalusia, then eastward to India.

Origin of the Arabic Numerals is a lengthy and generally interesting contribution to the ongoing discussion concerning the origins of Arabic numerals… (readers) will find an abundance of thought-provoking and valuable material between these covers.